These above words are quoted by Yinka Shonibare, a Nigerian-British contemporary artist known for his amazing artwork using African print fabrics in his scrutiny of colonialism and post-colonialism. What is commonly known as “African fabric” goes by a multitude of names: Dutch wax print, Real English Wax, Veritable Java Print, Guaranteed Dutch Java, Veritable Dutch Hollandais. I grew up calling them ankara and although they’ve always been a huge symbol of my Nigerian and African identity, I had no idea of the complex and culturally diverse history behind the very familiar fabrics until I discovered Yinka Shonibare and his art.

European imitation and industrialisation of Indonesian batik techniques

The development of the African print fabric has been referred to as the “result of a long historical process of imitation and mimicry”. How exactly Dutch wax prints became popular in West Africa is debated. What is known for certain is that Dutch wax prints started out as cheap mass-produced imitations of Indonesian batik locally produced in Java. Colonial powers, particularly the Dutch and the English, played heavy roles in industrialising the batik production techniques and popularising the resulting textiles in foreign markets.

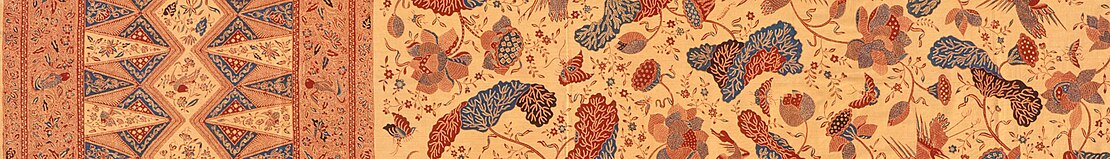

A typical coastal batik has vibrant colours with patterns drawn from numerous cultures

A typical coastal batik has vibrant colours with patterns drawn from numerous cultures(kain panjang with lotus motifs from Semarang, 1880)

Views differ as to how Dutch wax prints entered the West African market. One view is that in the late 1800s, Dutch freighters on their way to Indonesia from Europe stocked with their machine-made batik textiles stopped at various African ports, and subsequently an African client base grew.

Another suggestion is that the Dutch wax fabrics did not do as well as expected in the Indonesian market due, in part because of economic restrictions imposed on the sale of forign textiles at the beginning of the 20th century to protect locally made batik textiles. It has also been suggested that the industrialised wax prints were regarded as much poorer in quality that the locally handmade batiks. In order to prevent a loss, the target market switched to West Africa.

There is also the theorized role played by West African indentured soldiers for the Dutch in Indonesia, also known as the Black Dutchmen. They served between 1810 and 1862 and many had taken Indonesian batik with them on their return home as gifts for their families. Thereafter, local interest in the fabrics grew, and the Dutch wax prints were the closest imitation available. The role played by Black Dutchmen is questionable, however, because while a large number of them married Javanese women and stayed on in Indonesia, those that returned to their countries of origin usually came back empty-handed due to shortcomings and delays in salary payments from the Dutch.

Lest it seem that the introduction of Dutch wax prints into the West African market happened out of the blue, West Africa had always been a textile market, since fabrics have been important aspects of African social life for a very long time. As early as the 16th century, the English, Dutch and French were selling batiks and other types of textiles manufactured in Asia, such as the “guinea cloth” and Indian produced cottons from Pondicherry, now Puducherry, to West African markets. Thus consumers were quite accustomed to globally-produced fabrics. The introduction of Dutch batik-inspired wax prints lead to the peak of foreign-manufactured fabrics in West African markets in the 19th century.

Regardless of how Dutch wax prints precisely entered West Africa, one can conclude that they were originally intended for the Indonesian market but found a more enthusiastic market in the Gold Coast (modern day Ghana) where they became symbols of high quality and fashion. From the Gold Coast, these fabrics spread into other West and Central African markets.

The acceptance and growth of Dutch wax prints by West Africans

In the 19th century West Africans embraced these Dutch wax prints, using and assimilating them into societies as a part of culture and self-expression. The English were manufacturing and selling wax print textiles as well, but the Dutch brands were more popular. It has been suggested that the Dutch were viewed as the “well-meaning” traders with West Africa, since a lot of West African nations were under English or French colonial rule.

Dutch wax prints carried, and still carry, an enormous amount of prestige and this was mostly likely due to their uniqueness as part of an European industry producing for export markets solely in West Africa.

Dutch manufacturers of these fabrics thereafter made some changes to designs and motifs in order to cater to the tastes of their new African customers. As can be expecting making prints using motifs designed specifically for the African market took more time and effort. Earlier design motifs used plants and animals believed to be universal to all cultures. From the middle of the 20th century, though, more effort was made in making design motifs more authentic by using indigenous African textiles to create similar motifs. In the 1920s prints began to feature portraits of local community leaders and chiefs in their designs that people could buy in to celebrate their leaders. This tradition continued with portraits of African heads of states and prominent politicians used as design motifs starting in the 1950s.

Designs and motifs that became extremely popular and successful were given catchy names, and they had proverbs and slogans attached to them by West Africans traders in their respective communities, even though these appellations had nothing in common with the designs on the fabrics. Due to this integration of Dutch wax prints, they are said to be “authentically African” even though they were produced and designed in Europe, presumably by Europeans with little or no African input in terms of designs and motifs at the production stages.

Up until the 1960s, most wax prints sold in West Africa were being produced in Europe. Post-colonially, things changed. Currently, Ghana is home to several fine and high quality wax print manufacturers including Woodin, a subsidiary of Holland’s Vlisco and ATL which is a subsidiary of Manchester-based ABC textiles. Notice that even though these textiles are now manufactured on the continent, the companies that manufacture them are largely not owned by Africans.

Yet West Africa became the exclusive markets for Dutch prints and Dutch brands have dominated the West African market since the end of the 19th century where they held importance as status symbols. Today, wax prints carrying European brand names are the most expensive in the West African fabric market. The Dutch brand Vlisco is a symbol of class on par with any popular Western brands like Rolex or Louis Vuitton. A wealthy person cannot be seen wearing just any wax print brand, it has to be Vlisco.

The Chinese entrance into the wax print market

It hasn’t been too long since Dutch wax prints started being produced on the African continent but now the African textile industry is facing competition from China. The entrance of Chinese manufactured print textiles brings another complication into the mix, throwing a wrench in the established trade networks between West African and European cloth manufacturers.

How the wax prints produced in China came into West African markets is another long story which can summarised thus: some African traders travelled to regions in China such as Shandong to reproduce fabric samples cheaply, which were to be sold in their respective countries. Thus, African traders had a role to play in introducing Chinese manufacturers into the African textile market.

With Dutch wax prints being increasingly reproduced in China, wax prints carrying ‘made in Holland’ tag are at the high end of the market, with Chinese productions occupying the opposite end. However, this is changing rapidly as the quality of Chinese wax print copies is apparently improving. The manufacturer based in Manchester was recently bought by a Chinese company, leaving Vlisco as the only European-owned producer of wax prints.

The question of authenticity

Dutch wax prints are of foreign origin but are widely recognised as African fabrics. To bring back the earlier quote from Yinka Shonibare; “an image of ‘African fabric’ isn’t necessarily authentically [and wholly] African”. Or is it? Delving into the history of Dutch wax prints and their strong popularity in West Africa draws questions of authenticity and “Africanness”. Are these fabrics African because they are popular in Africa? How does the fact that they started out as imitations of Indonesian/Javanese batik designs and were brought into the West African market by colonial Europeans fit into all this?

Though they seem to be quite unpopular, there are some voiced concerns with regards to an exploitative relationship with the European fabric markets. This article for example argues that what we call African wax prints are Javanese in production techniques and are a product of Javanese, Indian, Chinese, Arab and European artistic traditions. It calls for a “regeneration of authentic African print designs”.

This is where the question of authenticity comes up. Are Dutch wax prints really based on a traditional African form? Can they be compared to indigenous African fabrics such as the Yoruba adire or the adinkra cloth of the Ashanti? Has the introduction of Dutch wax prints hurt the indigenous textile market, driving locally produced fabrics out of the market? Actually, I’m tempted to answer ‘yes’ to the latter because I have been told that the adire textiles I own are out of fashion. The last time I wore hand woven aso-oke was more than a decade ago. Aso-oke is still worn at weddings and special ceremonies but they are not extremely popular, not as Dutch wax prints. After all I only see billboards for Vlisco and Da Viva .

It is no secret that I love fabrics and textiles. I try to buy Dutch wax prints that were manufactured in Ghana. At the same time I purchase locally-made fabrics not caring whether or not they are in vogue.

|

| Girl wearing aso-oke |

By Eccentric Yoruba

Solua likes to shares her favourite artists, so here is some more african music with handsomely dressed singers:

Ladysmith Black Mambazo - Vela Nsizwa

Sem comentários:

Enviar um comentário